Building confidence in animal free innovations – does requesting animal data to justify publication of a non-animal method help?

The 11th World Congress (WC11) on Alternatives and Animal Use in the Life Sciences recently took place online with the five themes of the congress being Safety, Disease, Ethics, Welfare and Regulation and Innovative Technologies. Both Dr Pandora Pound and Rebecca Ram from Safer Medicines Trust presented at WC11 and future blogs will discuss the subject of their talks in more detail. Their slides can be seen here.

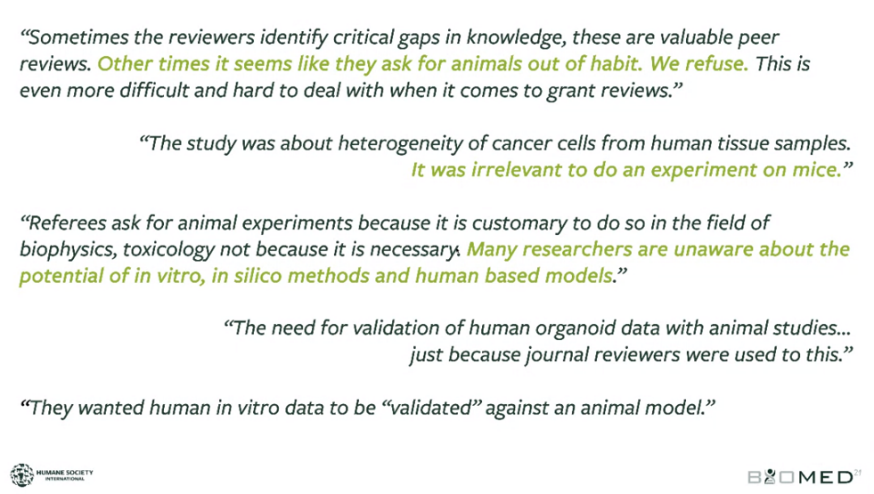

Speakers noted that some of the challenges to building confidence in animal free innovations were about the innovations themselves, in other words the new methodologies need to be valid, reliable and fit for purpose. However, an important topic addressed during the conference, was the need to change the mindset and policy of those who review research papers about new, animal-free innovations, i.e. peer reviewers and journal editors. It was noted that reviewers and editors frequently demand that additional animal experiments are carried out in order to validate in vitro, human-based new approaches before a paper is accepted for publication. Clearly this is a completely inappropriate, but apparently widespread issue; over 50% of academics surveyed reported that they had been asked for this extra work to be carried out following review of their manuscripts. Some comments from these authors were presented at the conference in a talk by Marcia Triunfol, from Humane Society International:

Triunfol reported that when asked why, most reviewers admitted they were unaware of new technologies that could be used instead of animals. Lack of understanding of these human-biology based approaches, status quo bias, journal editorial policy, scientific justification, regulatory requirement and avoiding sunk costs (animal facilities/husbandry etc) were all suggested as playing a part in perpetuating the practice of demanding animal studies.

The session panel suggested potential solutions could include a commitment by journals to scrutinise, and demand a higher level of justification for, reviewers’ requests for animal data and to publicly disclose when such requests are made. In line with these discussions, another recommendation was to educate funding agencies about the power of human-focused technologies, to encourage a better understanding of these novel approaches and ultimately their widespread adoption. Ironically, it was claimed that the United States’ primary medical research agency, the National Institutes of Health, has no funding streams totally dedicated to NAMs and that often grants are not given unless animal work is included in the project proposal.

Clearly something needs to be done to break these practices which continue to rely on animal data, often for unjustified reasons, and which are preventing more relevant, human-biology based methods from seeing the light of day.

Related: Organ chips, organoids and the animal testing conundrum